Connected Learning

- Julie Stivers, middle school librarian at Mt. Vernon Middle School in Raleigh, NC

- Miles, a rising high school junior and former student of Julie’s

- Kym Powe, Children and YA Consultant, Connecticut State Library

- Juan Rubio, Digital Media and Learning Program Manager, Seattle Public Library

- Sandra Hughes-Hassell, Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Information and Library Science

- Hold onto why you do the work.

- Recognize structural aspects of fostering equity and inclusion and simultaneously equip library staff to take individual action.

- Center the voices and experiences of youth themselves.

- Attend events like the Connected Learning Summit.

- Look for free professional development like Project READY.

- Talk to your state library.

- YALSA Article describing #LibFive

- Images of Practice: #LibFive at Mount Vernon Middle School (featuring youth researchers!)

- #LibFive Infographic

- VRtality website

- Article in American Libraries about VRtality

- “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces”

- Project READY: Reimagining Equity & Access for Diverse Youth

- GELS: Growing Equitable Library Services

- Equity Literacy Institute

- Project ENABLE (one of the models for Project READY!)

- WebJunction

- Radical Hospitality

- Racial Equity Institute

- EmbraceRace

- What Is Connected Learning?

- How Connected Learning Happens in Libraries

- Connected Learning in Libraries: Changes and Challenges

- What Is Connected Learning?

- How Connected Learning Happens in Libraries

- Connected Learning in Libraries: Changes and Challenges

- …they must be ready and willing to transition from expert to facilitator…

- …[they] need to apply interdisciplinary approaches to establish equal partnership and learning opportunities that facilitate discovery and use of digital media…

- …they should be able to develop dynamic partnerships and collaborations that reach beyond the library into their communities…

- …they should be able to evaluate connected learning programs and utilize the evaluation results to strengthen learning in libraries… (Hoffman et al., 2016, p. 19)

- What Is Connected Learning?

- How Connected Learning Happens in Libraries

- YOUmedia Chicago

- Young Urban Scholars book club

- An afterschool program for inner city, middle school students to imagine STEM’s relevance in their lives

- Hack the Evening

- Publications from ConnectedLib

- “Common endeavor, not race, class, gender, or disability, is primary” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 85). People in the affinity space relate to each other based on common interests, while attributes such as race, class, gender, and disability may be used strategically if people choose.

- “Newbies and masters and everyone else share common space” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 85). People with varying skill levels and depth of interest share a single space, getting different things out of the space in accordance with their own purposes.

- “Some portals are strong generators” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 85). People can create new content related to the original content and share it in the space.

- “Content organization is transformed by interactional organization”(J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 85). Or “Internal grammar is transformed by external grammar” (Gee, 2005, p. 226) Creators of the original content modify it based on the interactions of the people in the space.

- “Both intensive and extensive knowledge are encouraged” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 85). Specialized knowledge in a particular area is encouraged (intensive knowledge), but the space also encourages people to develop a broad range of less specialized knowledge (extensive knowledge).

- “Both individual and distributed knowledge are encouraged” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 86). People are encouraged to store knowledge in their own heads, but also to use knowledge stored elsewhere, including in other people, materials, or devices, using a network of people and information to access knowledge.

- “Dispersed knowledge is encouraged” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 86). One portal in the space encourages people to leverage knowledge gained from other portals or other spaces.

- “Tacit knowledge is encouraged and honored” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 86). People can use knowledge that they have built up “but may not be able to explicate fully in words” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 86) in the space. Others can learn from this tacit knowledge by observing its use in the space.

- “There are many different forms and routes to participation” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 87). People can participate in different ways and at different levels.

- “There are lots of different routes to status” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 87). People can gain status by being good at different things or participating in different activities.

- “Leadership is porous and leaders are resources” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 87). No one is the boss of anyone else; people can lead by being designers, providing resources, or teaching others how to operate in the space. “They don’t and can’t order people around or create rigid, unchanging, and impregnable hierarchies” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 87).

- People in a passionate affinity space interact around shared goals because of a shared passion, not because of shared backgrounds, age, status, gender, ability, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, or values unless these are integral to the passion.

- Not everyone interacting in the space need have a passion for the shared interest (they could simply have an interest), but they must acknowledge and respect the passion and the people who have it and who form the main “attractor” for the space.

- People earn status and influence in the space because of accomplishments germane to the passion, not because of wealth or status in the world outside the space.

- The space offers everyone the opportunity, should they want it, to produce, not just consume, and to learn to mentor and lead, not just to be mentored and follow.

- People in the space agree to rules of conduct - and often enforce them together - that facilitate the other features above. (J. P. Gee, 2012, p. 238)

- “A common endeavor for which at least many people in the space have a passion - not race, class, gender, or disability - is primary.” (p. 134) Gee and Hayes assert that the passion in an affinity space is for the endeavor or interest rather than the people; in nurturing affinity spaces, participants in the space understand that “spreading this passion, and thus ensuring the survival and flourishing of the passion and the affinity space, requires accommodating new members and encouraging committed members” (p. 135). Affinity spaces that are not nurturing may treat newcomers poorly or restrict access to participation according to experience.

- “Affinity spaces are not segregated by age.” (p. 135) In a nurturing affinity space, older participants in the affinity space set norms of “cordial, respectful, and professional behavior that the young readily follow” (p. 135) while in other affinity spaces, knowledge accrued with age may not be readily shared.

- “Newbies, masters, and everyone else share a common space” (p. 136). Nurturing affinity spaces make it easy for newcomers to participate, avoiding hazing or testing new participants.

- “Everyone can, if they wish, produce and not just consume.” (p. 137) Nurturing affinity spaces set high standards for production, enforcing them through “respectful and encouraging mentoring.”

- “Content is transformed by interaction.” (p. 137)

- “The development of both specialist and broad, general knowledge is encouraged, and specialist knowledge is pooled.” (p. 138) Within a nurturing affinity space, specialists understand that their knowledge is partial, and everyone pools their knowledge by sharing it in the space.

- “Both individual knowledge and distributed knowledge are encouraged” (p. 139). “Nurturing affinity spaces tend to foster a view of expertise as rooted more in the space itself or the community that exists in the space and not in individuals’ heads” (p. 139)

- “The use of dispersed knowledge is facilitated” (p. 140).

- “Tacit knowledge is used and honored; explicit knowledge is encouraged” (p. 141).

- “There are many different forms and routes to participation” (p. 142).

- “There are many different routes to status.” (p. 142)

- “Leadership is porous, and leaders are resources.” (p. 143)

- “Roles are reciprocal.” (p. 143)

- “A view of learning that is individually proactive but does not exclude help is encouraged.” (p. 143)

- “People get encouragement from an audience and feedback from peers, although everyone plays both roles at different times.” (p. 144)

- “A common endeavor is primary.” (p. 48)

- “Participation is self-directed, multifaceted and dynamic.” (p. 48) Participants in an affinity space do not only participate in existing portals, but may build their own portals to generate content.

- “In online affinity space portals, participation is often multimodal” (p. 48). Contrasting Gee’s research on early text-based discussion boards as portals, Lammers and colleagues point out that participants in contemporary affinity spaces may produce not just text, images, websites, or maps as in the affinity spaces Gee originally described but also videos, maps, podcasts, and machinima.

- “Affinity spaces provide a passionate, public audience for content.” (p. 49)

- “Socialising plays an important role in affinity space participation.” (p. 49)

- “Leadership roles vary within and among portals.” (p. 49)

- “Knowledge is distributed across the entire affinity space.” (p. 49)

- “Many portals place a high value on cataloguing and documenting content and practices” (p. 49).

- “Affinity spaces encompass a variety of media-specific and social networking portals” (p. 50).

- “That the important activity in an affinity space is only that which contributes directly to the group’s shared interest or common endeavor” (p. 410)

- “That the development of strong bonds among participants in an affinity space is necessarily subordinate to taking part in the group’s shared interest or common endeavor” (p. 410)

- “That affinity spaces are largely stable entities, confined to single sites or discussion boards” (p. 411)

- They are specialized, focusing on a specific affinity or interest.

- Involvement in them is intentional; participants choose to affiliate with the network and can move easily in and out of engagement with the network.

- “Content sharing and communication take place on openly networked online platforms” (p. 42) New participants can find the networks on the open internet and do not have to enter into a financial transaction or have any specific institutional membership in order to participate.

- Strongly shared culture and practices

- Varied ways of contributing

- High standards

- Effective ways of providing feedback and help (p. 17)

- “Purpose-driven participation” (p. 174)

- “Diverse forms of contribution and participation” (p. 175)

- “Community-driven ways of recognizing status and quality of work” (p. 175)

- “Competitions, creative production, and civic engagement” (p. 178)

- Getting rid of disposable assignments

- Opportunities to communicate and collaborate

-

- Competition

- Production

- Peer-support

- Interest-powered learning

- Community

- Openly-networked supports, provided both my the designers of the game and the community of players

- Social interaction and expertise that translates across contexts (home, school, public IRL, online)

- What factors facilitate the connected learning experience of members within the group?

- How does the public library as a location for the meetup group affect the participants’ learnign experience?

- What are challenges and barriers for connected learning as experienced by the group, and how can libraries address those? (p. 3 in author’s copy; consult published version for final page number)

- Increasing the awareness of social learning opportunities within a learning environment

- Facilitating an open, collaborative and interactive culture among users in learning environments

- Providing access to contempoerary learning tools and materials for “learning-by-doing” activities

- Supporting informal socialisation and hangouts between participants inside as well as outside the learning space premises and opening hours (p. 25 in author’s copy; consult published version for final page number).

📚 Finding my throughline: Library enthusiast 💻

I recently listened to Katie Rose Guest Pryal on Camille Pagán’s podcast, You Should Write a Book, talking about how she found the throughline in her work and life. (Just listen to her articulate it on the podcast. I am afraid if I try to sum it up, I’ll get it wrong.)

At the time I listened to it, I was like, “I don’t know what mine is. Maybe I’ll never find it. Waaaah!”

But as I sat and let the idea marinate for a while, and I think I’ve figured it out.

I recently bought the above sticker and several other library-themed stickers, as well as a Read Free or Die t-shirt, from its creator.

One of the possibilities I was considering for after my postdoc was going back to being a school librarian. I don’t think that one’s going to pan out, but it did sort of launch me in the direction of identifying my throughline.

In May, several folks working on different grants funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services, including myself, met and talked about what we’d learned from our work and what our capacity was for working on connected learning in libraries moving forward. All of the other academics indicated that they had to move on to other work, which might incorporate connected learning, but would not focus on it.

I found myself heartbroken.

This is what I want to work on. And nobody else, nobody with an institutional affiliation, was going to be able to work on it anymore?

Well.

Over the course of many weeks, I decided that I would still work on it. That I would find institutional partners who were willing to do a little bit of the work, so that I don’t have to have an institutional affiliation myself to get the work funded, but that I would be happy to do the bulk of the work so long as I could get a consultant’s fee for doing it. Enough to pay my student loans, mostly.

I’m in the process of refining this vision.

But the throughline, I’ve got that now.

Fine, it needs refinement, too, but here’s the basic idea:

My work builds libraries' capacity to facilitate learning and connect with their communities. The two modes I use to do this are research and professional development.

This describes so much of what I’ve done for the past 8 years. And more than that, it describes what I want to do going forward. It’s expansive enough for me to take on a variety of projects, and narrow enough that I can continue to establish my areas of expertise and grow my network.

What’s your throughline?

#CLS2022: Creating Equitable and Inclusive Library Spaces in the Face of Obstacles

I didn’t get to liveblog/tweet this session because I was co-facilitating it, but I’m jotting down a few takeaways and a list of resources/links in hopes they will be of use to folks.

Our panelists were:

We opened by asking the panelists to share their broad perspectives on creating equitable and inclusive library perspectives.

Connected Learning Lab Senior Research Manager Amanda Wortman took awesome notes on these. Here are some big ideas:

We then launched into some questions based on our work in the Transforming Teen Services for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion project. I basically acted as a clueless, well-intentioned librarian asking for help.

How do I know if I’m actually creating an inclusive space?

You might not be able to tell, but if your love for the work shines through, you’re moving in the right direction. When your space starts to feel like a living room and a community hub, keep doing what you’re doing and grow more in the same vein. Look at yourself and your colleagues; what unstated or invisible expectations are you communicating? They might be making the space less inclusive.

I think I’m creating inclusive spaces but people aren’t actually coming into them. What should I do?

LEAVE THE BUILDING. There are a lot of reasons people might not come. Go to where they already are. Consider not just your own actions, but those of your colleagues. Are other people in the space making it less equitable and inclusive? Build authentic relationships, in or out of the library. The relationship with the person is more important than the presence of the physical space. Change the power structures in the space; design with youth rather than for them.

I know I need to leave the building but I’m overwhelmed. How do I start?

You start by starting. Team up with a friend. Build on the work of a colleague near or far who has already gone out; learn from their experiences. Don’t stop going out after one attempt doesn’t work. Move on to the next potential place or partner. Keep trying. You’ll eventually find the right fit.

Okay I’m ready! But I talked to my supervisor and they said I can’t leave the building. What’s my next step?

Relationships are important here, too. Build a relationship with your supervisor. Help them understand the value of the work you’re doing and why it’s important to go into the community. Write a formal proposal for the supervisor. Include outcomes and impact. Make it clear it won’t take you out of the building for a whole day at a time.

How can school and public librarians think beyond just going into each others’ spaces? How can we get to places that don’t have library or school vibes?

Go to where they spend time outside of school. If you’re partnering with a school, think about going to extracurricular events that don’t feel so formal and school-y. Recognize that what matters most is that youth get what they need, not who provides it or where.

I want to learn more! What should I do next?

Links

My Notes from #CLS2022: OPENING PLENARY - Staying Connected, Fueling Innovation, Affirming Core Values: Three Learning Organizations Carrying Lessons Forward from the Twin Pandemics

Getting today's plenary started - Staying Connected, Fueling Innovation, Affirming Core Values: Three Learning Organizations Carrying Lessons Forward from the Twin Pandemics

is moderator, beginning the panel. Talking about carrying forward lessons from pandemic crisis into "neverending pandemic."

invites attendees to share something good that came out of the pandemic for them. There are too many to share all here! But big themes are family time, taking breaks, conversations about accessibility.

Jessica, let's start with you. We think of a library as a physical space where people go. What happened with your library during the pandemic? What can other people, in a library or otherwise, learn from your experiences?

works with Cloud901, a teen learning lab in Memphis Public Libraries, work with STEM/STEAM, project-based learning, and connected learning.

Closed for about a month, partnered with other city divisions & community organizations. Metropolitan Interfaith Association - library staff boxed food, were drivers, were able to get into community with access to library materials, worked with p

Worked with Parks & Rec and other divisions to disseminate information about social services. A great opportunity to get out and reach out to communities who were underserved or couldn't readily come to the library.

Previously divisions were siloed but now they can connect to serve the community.

Shifted to online programming. With that program, they touched people in communities across the country, not just Memphis.

Able to work with people who wouldn't normally come to the library for a myriad of reasons - anxiety in social settings, other reasons - able to access library programming at a comfort level that worked best for them.

A lot more families at online programming. A lot of parents working alongside kids during camps. Opportunity for family to get together & bond and parents became library advocates.

Understanding & seeing that library staff need to recognize in every aspect where barriers are, even when we don't readily see them.

Online programming was wonderful, but what about people without home internet? What about requiring supplies for a program?

What barriers are out there? How can we break those down? Wifi hot spots, takeaway supplies. Producing programs that only use things readily available at home or brick & mortar store.

With population 30-40% below the poverty line, people have to choose - do they send their kids to an enrichment opportunity, or do they feed them?

Really promising: holistic vision of youth & families & what they need. Intersection of innovation and equity. "We can't do this for everybody, so we're not going to do it at all." So iterate to make it accessible for more people.

runs a clubhouse that had to move online. It was a challenge. Hearing some commonalities between ListoAmerica, an afterschool program that serves primarily Mexican community, and library already.

ListoAmerica is part of The Computer Clubhouse, a network. Had to shut down physical space, but within about 2 - 3 weeks, UCI PhDs were able to support creating the clubhouse online for the same hours online.

Tried to replicate as much as possible the pre-pandemic experience but had to be innovative. Started member-to-member meetups because new members would be isolated.

Members are youth. Usually middle school & high school. Connected new members with mentors.

Created hybrid programs. Created pick-up point for materials to pick up at one time and conduct sessions later on.

People would make themselves available in online community at specific time so other people could come discuss with them.

Temptation is to just learn the technology and gain skills, but goal of ListoAmerica is to support creation, not just skill building. Connect people with interests - for example music-interested youth and video-interested youth collaborate on music video.

Mexican culture is important. Mentors were almost all Mexican. Mexican American members often had parents who were undocumented and thus didn't want to come in. Mentor created entire Discord channel in Spanish and invite family members in.

works in Tacoma school district in Washington State. Fortunate to have a school board and superintendent who embraced pandemic as a community with grace and empathy.

In March 2020 decided to be as pro-active as possible. Set up design around an online school that they expected to have about 400 kids, ended up with about 5000 out of 30000 who wanted an online experience.

over 250 staff members, community eager to keep students safe in the online world. Quickly shifted gears into evolving into high quality. It was difficult because staff hadn't been trained in online teaching.

Grace for staff and students formed a community. While other districts are sprinting back to "normal," Tacoma has moved toward redefining and reimagining new normal.

Online school is now a fully-functional school with about 2000 students. Tacoma is also introducing a flex program to allow students to experience both face-to-face and online learning, which allows flexibility in their schedules.

Tacoma's been working on a whole student initiative and this moved them toward a whole community perspective.

When is an online environment better than an in-person environment? When is it a weak facsimile of a personal environment?

Didn't think online clubhouse would work, for example "creative collision" in small space where people would bump into each other and notice each others' work and ask about it.

Somehow, with the hybrid model, it worked. Occasionally, we would get together in very careful (socially distanced, masked) groups, and were able to go global. Connected with clubhouse in Mexico City. Never were able to do that before.

That enhanced the cultural background, that it's okay to be Mexican in the United States, it's something to be proud of. Opened Mexican American citizens' eyes to what it's like to be in Mexico and what technology is like there.

Able to connect online with people from all over. Were able to ask colleges to send virtual tours for them to share with people who couldn't travel to visit.

This summer, they started back in person with summer camp. Every camp this year people have come back with people they met in camp and they've continued to work together. This didn't happen before.

It's a "Yes, and." Redefined understanding of connected. Multitiered opportunities to connect with adult learners, assessing online experiences combined with occasional face-to-face meetings led to some simple tech innovation.

Kindergarteners took a field trip to the zoo, some in person, but many remotely who were working in teams and engaging during chat because the schools had taught that school. Recorded the session and now it can be reused with different groups.

Online learning is not the best path for every kid, but it very well could be for some.

Teachers were not only livecasting, but were interacting with students online. Students could see their own teacher.

Was the number of participants the same, larger, smaller, different people in online programs versus face to face?

Old members already had established connections. New members would introduce themselves and old members would connect with them.

Scale expanded going remotely. The question now is should we go back to some form of physical?

It depended on the program. Camps were larger than we anticipated. Some other programs like college virtual tours were huge numbers. Some programs just had 2 to 3 people in them. We counted it as a win whatever it was.

Club and extended learning opportunities tended to grow online.

Transitioning to online was already a struggle, so any number of kids we counted as a win.

We've gone back to in-person but there will always be some kind of hybrid component to a good bit of our programs.

We didn't have multiple-hour programs. They were very short, intensive. We would talk, but the staff made a lot of video work that youth could not only watch, but reference.

Having videos to reference helped kids who fell behind or missed sessions. We shared it with other library systems in Tennessee.

Have there been opportunities to connect and collaborate with parents and other community organizations?

We had existing partnerships and it was exciting to see those partners pivot with us.

One thing that's worked for us is other non-profit engagement. We got a call from an organization in another county that wants to open up a clubhouse and a remote clubhouse working with us.

Final thoughts?

What we have found is that for us, there's no "getting back to normal." There's working to address the shift in our youth. We've seen a number of youth ask for programming and services around mental health, being engaged with social & economic issues.

We're shifting and rebuilding in some areas with how we continue to service our youth. What we did before for branding & strategic planning can stay in place but we recognize that the way we were doing it needs to shift.

A young lady who started with us in middle school and is now at Cal State University Fullerton, whose world was a 2-mile radius when she started with us, now has a global perspective and spent a semester in South Korea.

It's a vulnerable celebration of acknowledging that we don't know what we don't know. Adam Grant: "We live in a rapidly changing world where we need to spend as much time rethinking as we do thinking."

My Notes from #CLS2022: Rising Scholars - Post-Pandemic Life: Recovering From Burnout and Finding Motivation

Introducing the next Rising Scholars session: Post-Pandemic Life: Recovering From Burnout and Finding Motivation

About to start as Asst Prof of learning sciences @ Univ of Buffalo, working on the ways crafting/art-making/design activities can interact with & enhance learning equity in both formal & informal spaces.

Spending a few weeks with family moving into the new position has been a good boost at this point in the pandemic.

Dr. Mackey is a postdoc scholar w/Equitable Futures Innovation Network @ Rutgers but is based in Colorado (hello fellow remote postdoc), co-founder & ED of Young Aspiring Americans for Social and Political Action. Mother & partner.

Whatever I'm engaging in & whoever I'm engaging with must honor that my soul has to be connected to the work.

My wellness matters, especially for me to be a mom, which is my legacy, my most important work. (Dr. Mackey is speaking to my heart.) Putting transition time in between meetings. Doing phone calls instead of Zoom in order to b

Doing phone calls instead of Zoom in order to move away from the desk. Quoting Toni Morrison: "The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work." Dr. Mackey is refuting whiteness and focusing on Black fine

Dr. Tanksley is an Asst Prof at UC Boulder & also faculty fellow at UCLA Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, working on critical race in education, sociotechnical infrastructure impacting youth.

Dr. Tanksley lives in LA and works digitally, always working with Youth of Color in urban settings.

Dr. Tanksley builds a schedule based on healing: sleeping in, daily getting an "overpriced, decadent-ass coffee" at a BIPOC, queer coffee shop and writing there. Nap, administrative work in the evening.

This is how Dr. Tanksley deals with the multiple pandemics and "the constant fuckery of the US." Asks: what can I do to make my life joyful?

Working with Black youth laughing and cutting up is healing, too.

BTW if you're near me in Durham, NC check out Rofhiwa Book Café for your own decadent-ass BIPOC queer coffee shop coffee. (I have bought books from them but haven't been in yet.)

What are some other things the panelists are doing like Dr. Tanksley talked about?

Reading for pleasure.

Being careful about who I work with, what contracts I take.

Eased into reading for pleasure with audiobooks.

Returning to things I loved.

It doesn't seem like there's an end in sight but we'll make it.

Mentor said "You're not going to be able to read for pleasure in grad school" but I do it just to prove her wrong. Peloton has gotten me through a lot of this.

How have you maintained community during the pandemic?

My group chats flourished.

Virtual game nights didn't work for me - we were using the same platform I was using for work. Some of my friends have developed a really helpful way of saying what we need in a moment. "I need to vent. I'm not looking for solutions."

I have so many chats. Also Netflix. We were watching shows together and would pause and reflect on certain episodes, epiphanies, hot messes that happened. Collaborative healing sessions. Created in a digital space for youth after the killing of George Floy

Collaborative healing sessions. Created in a digital space for youth after the killing of George Floyd. Not for consumption; anyone in the space, including adults, had to be there for healing, not observing.

Building community for the purpose of connecting and healing.

It sounds like we're engaging in a lot of the same healing practices and communal practices.

Extraverted friends adopt me. These two colleagues with me at Boulder, we FaceTime almost every night. We'll call because something devastating happened and within ten minutes we'll be cracking up.

There's the healing you do in therapy, the healing you do on your own, and the healing you do with your friends. Sharing memes, talking shit.

Re: a paper that grew out of racism: "We're here because of sisterhood."

Laughing is a strategy we can use to get us centered.

I joined a virtual writing group specifically for Black women and that has been my saving grace.

How do you maintain motivation to push through your work during the pandemic?

I'm on leave right now. It's my second year on the tenure track. There was a lot of talk like "You don't need to take a break right now. You just started." In order for me to continue this abolitionist project, because it is a lifelong project, I

In order for me to continue this abolitionist project, because it is a lifelong project, I needed to take a break from the institution.

It's actually very common for people to take breaks in those first six years before tenure. They won't tell you that, but you're well within your rights to do that.

My work is soul work. It is tied to my community. It is tied to my deep-set dreams for emancipation. There's always motivation to do the work. It's about finding time to do the different pieces of the work. Every day is not. writing day.

Sometimes I read Twitter threads and that's my contribution for the day. There are pieces that we don't consider the work that are very important.

You have to think through "What am I motivated to do today?" even if it's taking a nap. That's part of the work, too. We're already talking about rest is resistance.

The faculty & institution are often going to make you feel like you don't have time for breaks, it's not possible, but it's important to stand firm in what you need.

It's okay to reconsider, make sure you see a path forward. Sometimes it's finish this dissertation and then figure out what's after that. Sometimes it's take a break from this dissertation.

I defended on March 12, 2020. I was anxious about the world and I had revisions. I took a break. I took a couple months.

The feeling is valid and whatever ways you need to manage that are also valid.

When I came into grad school, it was already a lot of unhealthy hustle culture. I'm going into tech. I don't have to hustle during a pandemic to write all these papers. I don't have the energy to think beyond this coursework and my research.

My energy tanks at certain parts, have some things that are research tasks, even if they're small, where I'm moving this thing forward even if it doesn't feel like a huge chunk of work.

If any of the panelists want to share how therapy have helped them manage anxiety, stress, all the things that have come up during the pandemic.

I have a life coach. He is always like, "What is going to make Janiece well?"

My life coach walks me through the saboteur voice, because I have assumptions. I'll say, "So and so might think this," and he'll say, "Okay, well even if they think that, why do YOU think that?" Being able to identify, name, & pivot away from that voice.

Also to delegate, because I tend to hold on to things that I shouldn't.

Mindfulness and yoga have helped me be mindful of what I'm holding onto physically.

I have been to therapy and I thought that it was helpful. In all kinds of communities, we don't talk about mental health.

Sometimes we get these messages that something has to be terribly wrong to go to therapy, and that might be true, but it also might not be.

Sometimes it takes time to find the right kind of therapy or the right kind of therapist.

There are resources online for folks who have had trouble finding a therapist. Finding a good therapist is hard.

If you feel at the end of the day you didn't do enough writing, rethink what writing looks like.

How do you all deal with pushback when taking breaks and doing things to help with burnout?

I tell people I can't pour from an empty cup. Either way the work isn't gonna get done, so I might as well pour into myself.

I go to therapy. I'm the caretaker of my family. I financially support multiple people, I caretake for my father who has a mental disability, I'm constantly the Strong Black Woman and I feel very uncomfortable unloading onto other folks who I caretake for s

I'm constantly the Strong Black Woman and I feel very uncomfortable unloading onto other folks who I caretake for because then I end up caretaking again. It's good to have somebody who it's low risk for me to give everything to.

I check my therapist sometimes because sometimes she'll say stuff and I'll say "What you're saying is wild and here's how you need to be caretaking for me."

When I say I need a break, I'm telling you. I'm not asking for a break. "You can tell me all the reasons it's not poppin', and I'm gonna say that sounds like a personal problem. Respectfully, I'm gonna tell you, I'm gonna take this motherfuckin' break."

It's not a common practice for them to just fire you because you want to take a break.

If I don't break, I'm going to break.

Any last thoughts or pieces of advice you have for people who are trying to recover from and/or manage their pandemic burnout?

Where is pushback coming from? Make sure it's not yourself. Find spaces and sources that replenish you. For me it was the water. I play my cello. Just to replenish my soul.

Say no a lot.

Not "No, because x, y, and z" but "No. Because I said so." We hear it all the time, but then it's really hard to do.

I haven't had repercussions for saying no beyond the awkwardness of saying no.

If you want to say yes but you don't have the capacity, find another way or delegate to someone who does. Be unapologetic. You know your limitations.

A helpful podcast for sleep: https://www.nothingmuchhappens.com/

Self-care has been commercialized, but I really Dr. Tanksley's approach around finding little moments of joy. I want to echo that. My last apartment had a beautiful tub and I started taking baths, I was like, "This is a mood."

We have to rethink these norms that we've put around things around taking care of ourselves and finding joy.

Don't overthink self-care.

Not feeling pressured to answer a text or a message if you're up and on your phone.

My Notes from #CLS2022: Rising Scholars - Exploring Pathways: Finding Your Place of Impact

introducing the panel Exploring Pathways: Finding Your Place of Impact

is a UX researcher at Google, place of impact with users in studies at work

UX researcher at Duolingo with ABC app focused on kids' reading in their native language, impact is with learners, kids, families, parents, teachers, and the product itself

works for Utah State University but lives in Long Beach, CA, does curriculum design, teacher education, and research, always exploring new pathways for impact

based in Bogota, Colombia, Associate Professor at Universidad Javeriana, research center in Colombia, and Berkman at Harvard. Impact follows a winding and networked pathway. Part of the Digital Media & Learning Initiative since the beginning.

I (Kimberly) love hearing how varied Andres's pathway has been! Focuses on projects & collaborations as much as positions/institutions. <3!

UX Researcher at YouTube working on fan-funding, also instructor and affiliated researcher at universities

What strategies/values/criteria did you use to navigate your own process of finding your place of impact? What helped ground you? What did you prioritize?

Find the heart of who you are and what you want to do and keep it at the center as you try a bunch of different things.

is knitting right now. I'm (Kimberly) crocheting right now!

goal was to support youth across their lives & now does so through curriculum design, teacher education, research.

Be open to relationships and opportunities. Sometimes you feel like you're pushing against a wall. Take a break from pushing against the wall and look for what's already open.

Making connections across spaces (eg families & institutions, communities & workspace) is the heart of Debbie's work. Allowing parts of life outside research to come through in research life.

Impact is a moving target in the face of change. Be attuned to your context. Grasp opportunities as they appear.

Pay attention to communities and mentors who give you space to join your interests.

It takes energy to keep finding projects, grow, connect, build communities.

Searching for the intersections where your impact will be takes time and work. Think about the types of impact you want your work to have, what outcomes do you want your work to have? Who do you want to be affected? In what ways?

YouTube team leveraged specific work from Jen's dissertation to impact product development and that was really exciting.

tried a lot of things out in grad school. Academic research, contributing to academic community & body of knowledge, direct impact on kids in classrooms, volunteered at conferences, TAed, volunteered in early childhood classroom, internships.

Applied to lots of different jobs, teaching postdocs at liberal arts, faculty at R1, UX at big tech company, research scientist at non-profit. Paid attention to what held a draw.

Started @ Joan Ganz Cooney Center impacting policy from 30,000 feet view, wanted next to get experience working on a specific project. Important to recognize that whatever you're trying now isn't something your locked into forever.

Any standout moments that led to the work you're doing now?

The interview process gave specific signal into whether community was energizing.

Unsuccessful job search led to postdoc with mentor Yasmin Kafai on e-textiles grants. Didn't get job at Cooney Center that Kiley did but DID get work from them doing a lit review with a colleague from a different grad school.

Sometimes saying NO is what leads you to your impact.

Echoes Wendy's point. Saying no clarifies priorities: I want to live in a particular place, I don't want to live away from my partner. Also echoes Kiley's point about gut checks.

How would you suggest going about finding opportunities to explore places of potential impact?

Try & apply to different things. Doing an internship during PhD program in a crisis led to connecting with a community of mentors and peers encouraging a networked, omnivorous mindset.

You need a lot of luck. The more that you try, the more opportunities you'll be able to grasp.

Sometimes the closed doors are powerful in opening up new opportunities.

Apply to jobs in places you might not have thought you would end up.

You might need to be more assertive than you would normally be, introduce yourself to people whose work you admire.

Relationships are important even if you have to foster them yourself.

Academic mentors are good at academia but you might have to look outside academia for people who can mentor you in other areas.

If you're following up on a connection, you may need to remind them how you connected before. You don't know where relationships will lead.

It might not be someone who is already in a position more advanced than yours. Might be another student or someone you met when you were both students.

How important were relationships to finding your opportunities? How did you navigate the awkwardness of asking for referrals or help finding positions? How did someone else extend an opportunity for you in a way that felt graceful?

Make connections BEFORE the exact opportunity is available. Don't wait until you see a particular job. Build relationships with people who are making the kind of impact you want. That feels more genuine.

Relationships start early and you don't know where they will lead.

Maintain connections with people mentors introduce you to.

Sometimes you connect over hobbies - people just approach me because I knit publicly.

Approach people with deep respect.

For Andres: How do you make an impact in the diverse Colombian context? How do you meet the expectations of your boss and your own expectations?

There is a shortage of resources in Colombia. It can be difficult to find research funding. At universities you need to start negotiating your agenda as a researcher and balance it with the teaching aspects. The emphasis here is more on teaching.

If you can create your own non-profit/institution, you will have more control over your own priorities because there's not a boss to tell you no.

What last thoughts or pieces of advice do you have for people wanting to find their place of impact?

Be open to new opportunities. Find ways to blend and combine your multiple interests. Carve out space to have more exploratory or informational conversations with people.

Reaching out early sets you up for having relationships and networks later.

Find the heart that keeps you going. You will have to do things that aren't part of your passion. You will find places where your passion stretches out beyond your job. You can't predict where things will happen.

Protect that heart. Find ways that feel authentic to you. Be open to places that will connect with it that you didn't expect.

Find communities whose interests and heart resonate with yours. As you join them and exchange ideas, you may find the pathway that connects your personal interests with the places that you can have an impact.

Be open to learning through the experience. Through the experience of getting somewhere you might find what fulfills you in an unexpected way.

Things will change and that's okay.

What's one thing you're looking forward to continuing or trying new as you navigate your path?

Supporting and studying K-12 computer science teachers without having prior experience in K-12. Advocating for them through publications and academia. Find ways to support them, their creativity & impact on students.

My Notes from #CLS2022: Rising Scholars - Sharing Work Beyond Academic Publishing

Alexis worked on hackathons including the Make the Breast Pump Not Suck hackathon (love it!) and others to bring people together to hack policy, services, & norms related to postpartum experience.

loves Alexis's work. Breast pumps are awful! Jean is director of CompSci equity project at UCLA. Jean taught high school & middle school English and social studies and got excited about critical pedagogy & addressing systemic issues.

Jean's research focuses on equity issues in computer science education.

Jean's recent research tries to elevate the voices of youth who have been pushed out of the world of computing and are experiencing their first computing class in high school.

How can we push the tech industry to recognize that they are responsible for the ethical implications of what they create? How can we get involved in changing this? Jean wrote a graphic novel called Power On about teens + CS & CS heroes addressing inequity.

Cliff works in teacher education and the same project as Jean, also with YR Media where youth produce and create media.

Cliff's work is at the intersection of computational thinking, critical pedagogy, and creative arts expression.

Marisa shares about porous authorship structures as opposed to the black box model of academic publishing.

Co-design process is reciprocal, traditional publishing is extractive.

Takeaways: Who are you trying to reach? Why now? Who is the right person to distribute the info? What kind of media does your audience consume? When?

Santiago asks what resources were helpful to panelists in beginning sharing beyond academia.

All the work from YR media is meant to be shared with the public. Research focuses on pedagogy, curriculum, and process.

Cliff makes it a point to present to educators, publish op eds, trade pubs.

It's important to consider the writing style in trade publishing & for non-academic audiences to make it readable, break the mold grad school may have pushed you into.

Have conversations about your work with people outside of your work and relationships and partnerships can develop. "Academia's not necessarily meant to get you to be a public intellectual." Read more journalistic writing, academics who write trade books

"Academia's not necessarily meant to get you to be a public intellectual." Read more journalistic writing, academics who write trade books.

Think about who surrounds you. Are you only talking to other academics? Don't drop your non-academic friends & family. Meet people outside academia.

Jean was an avid reader of graphic novels & manga but hadn't written one before and had to learn to write a comic script instead of description.

"Graphic Novel Writing for Dummies"-type resources can be helpful to learn how experts in the medium work (like Neil Gaiman or Superman writers).

Academic publishers often do a small run like 400 copies. Other outlets have wider reach.

Popular media is a lot of eyes if the people who you're trying to reach consume that outlet. "Where are people's eyeballs?"

There's value in directly impacting fewer people, too.

There's the question of impact and the question of scale and how you should negotiate that depends on the project and your goals.

For the Breast Pump hackathon, the goal was to change the narrative of breastfeeding from personal choice to structural one (importance of employment policies, healthcare) and prepped for communicating with the media.

https://makethebreastpumpnotsuck.com/research

Another goal was to change the culture of the media lab because the breastpump project wasn't future-focused enough or was too weird; deliberately targeted academic publishing as well to push back against that perception.

How do you balance the output demands & needs of academia/academic publishing with these non-traditional forms of sharing your work? How do you communicate the impact and value of this work within the academic context? How do we move past the h-index?

Why should I spend so much time on the peer review process? How deep is that impact? It can feel hard to justify but toggling or balancing and using academic vocabulary with peers can sharpen our thinking about those issues.

You can increase citations to underrepresented scholars and include voices from outside academia when you author academic work.

"Balance doesn't exist in my life right now... COVID has made things work."

Jean has an academic position as a researcher but steps of advancement aren't tied to tenure because the work is grant-based. Getting academic AND non-academic audiences excited about a graphic novel because it's based on research & translating research is important.

Getting academic AND non-academic audiences excited about a graphic novel because it's based on research & translating research is important.

I'm excited that my first, maybe only book, is a graphic novel because the kids in my family are reading it.

It's a graphic novel published by an academic publisher (MIT press).

We need to speak to academic audiences AND other audiences. Be intentional and strategic.

Being at a liberal arts institution is different than being at an R1. What department, school, or college you're in will affect what kind of output is considered as impact.

Some institutions will value podcasts and other media.

published an academic paper about the breastpump hackathon and followed that with a toolkit for people who want to host hackathons. It can be helpful to think through things as you write academic work and then leverage that thought process when writing popular work.

It can be helpful to think through things as you write academic work and then leverage that thought process when writing popular work.

What advice would you give to early career scholars who want to pursue academic careers and also sharpen their skills for creating art/writing outside academia?

You panelists are inspiring. Who inspired you?

Mike Rose from UCLA. Both Cliff & Jean had him as a professor. He translated academic knowledge to a mainstream audience. Cliff learned about the writing process from him.

How do I convey through storytelling the same message as research, but in a powerful, motivating, engaging way?

Mike was always practicing the art of beautiful writing. Every day he was writing on a yellow notepad with a pencil. It wasn't an egotistical, egocentric practice. He was thinking deeply about the people he had met & trying to convey their stories.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mike_Rose_(educator)

Artists we enjoy like David Bowie, Yayoi Kusama. Re-read books like you want to write - Jean re-read the March trilogy. Be inspired by the different ways a story can be told.

Catherine D'Ignazio (<3 Data Feminism)

Mitch Resnick & Natalie Rusk

Get in the habit of doing primary ethnography, engage with real people in real life that you're accountable to, transcribe your conversations with them, it's transformative for you as a speaker & them as a listener.

The Shakers thought about rendering their own religious views through arts, which is close to the practice of making public scholarship.

Ethan Zuckerman had students practice non-academic writing

Sarah Pink's Sensory Ethnography

Fostering Information Literacy Through Autonomy and Guidance in the Inquiry and Maker Learning Environments - Koh et al, 2020

Koh, K., Ge, X., Lee, L., Lewis, K. R., Simmons, S., & Nelson, L. (2020). Fostering Information Literacy Through Autonomy and Guidance in the Inquiry and Maker Learning Environments. In J. H. Kalir & D. Filipiak (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2019 Connected Learning Summit (pp. 94–101). ETC Press.

This is a quick note that I’m really excited about this conference paper I found that builds a bridge between connected learning (my broad research interest) and information literacy (my specific disciplinary interest). I’m going to explore it more and dig into the connection later, but I’m psyched to find a new paper on this.

Theory to practice: Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good

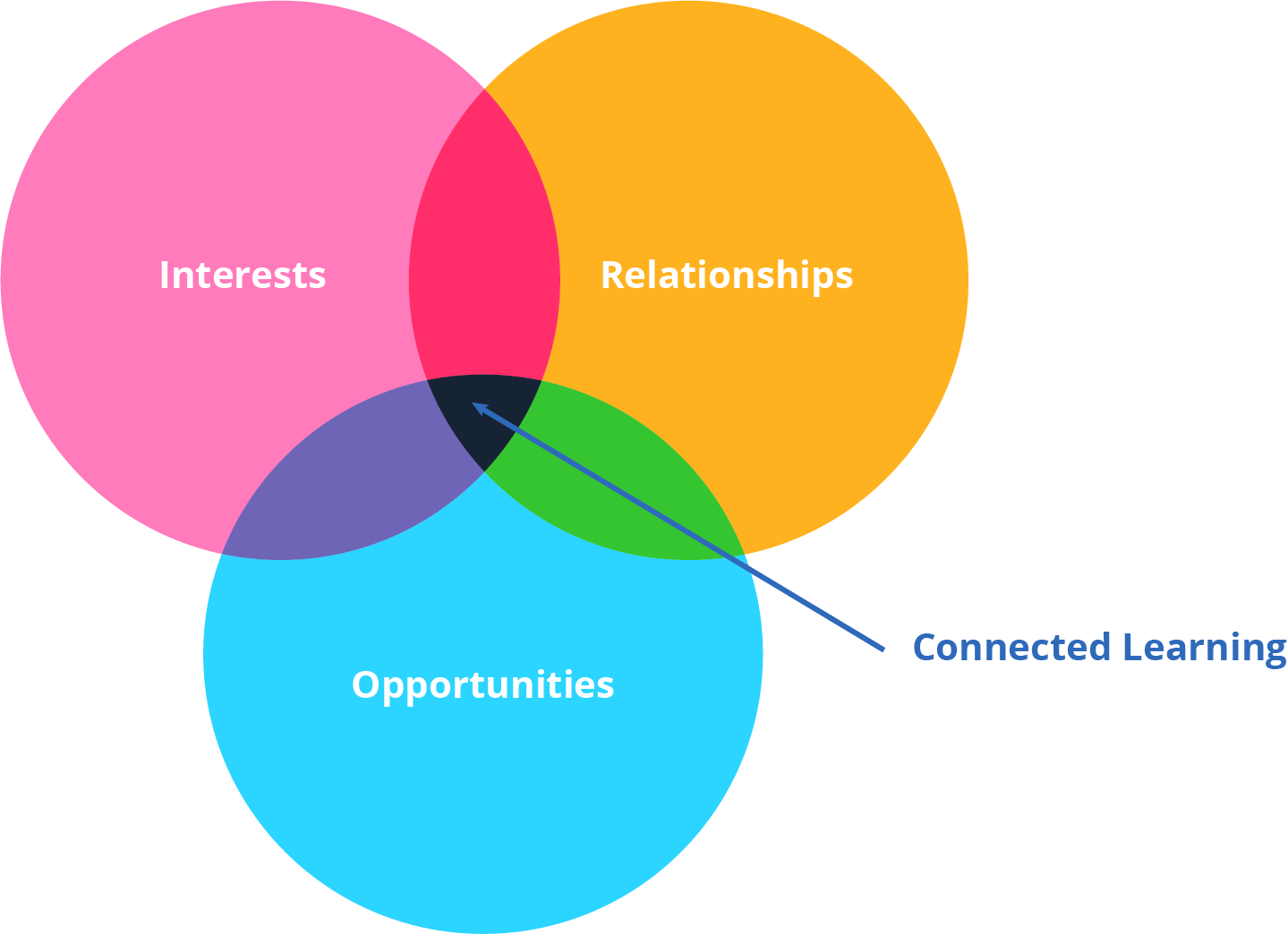

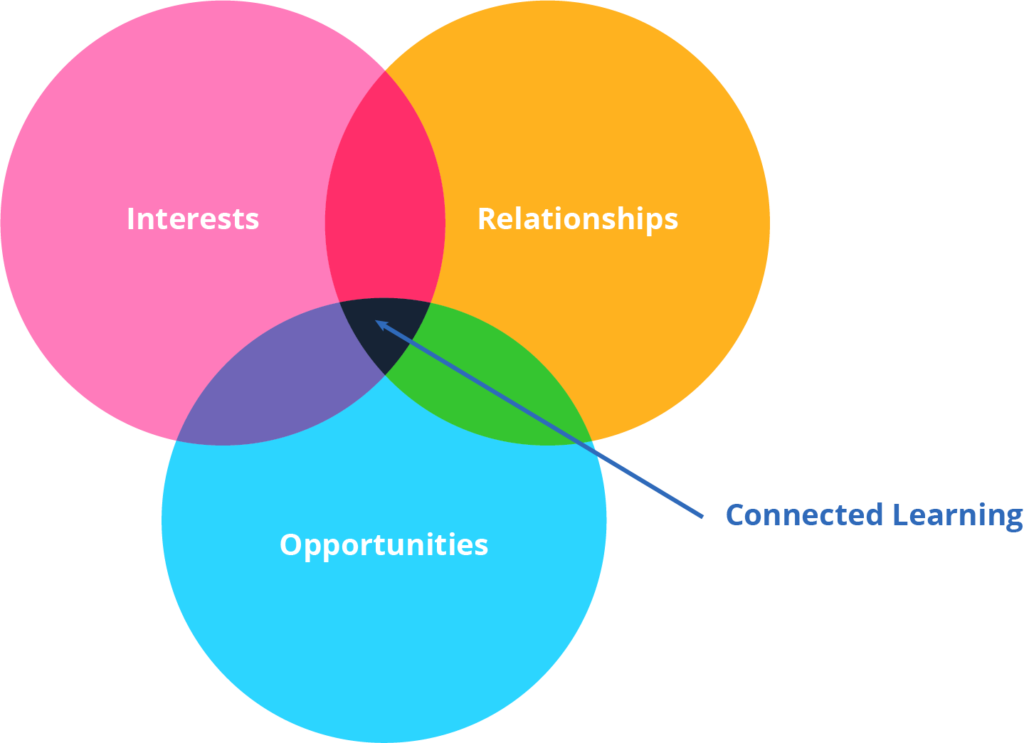

As we work on the Transforming Teen Services for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion project, one thing I have to be reminded frequently is that creating Connected Learning programming does not require providing for all three spheres: interests, relationships, and opportunities. Frameworks like Connected Learning begin as more descriptive than prescriptive: they say, “This is what’s been happening,” not “This is the only way to make it happen.” People like myself latch onto the aspirational qualities of this description and feel that if they can’t create a Connected Learning experience that encompasses the whole model, we shouldn’t even bother trying.

WE ARE WRONG.

Interests are the sine qua non of Connected Learning, so if librarians or educators start there by genuinely figuring out what youth are interested in and building their programming around that, they’ve gotten started in that direction. When CL happens spontaneously, the relationships and opportunities often come about through the course of the activity. When I started doing community theater as a teenager, I built relationships with peers and adult mentors and I had opportunities to learn things about theater production, to serve on non-profit boards, to act as a stage manager and a publicist. These aspects were not built into the environment explicitly for my benefit; they were natural byproducts of me participating in my interest.

So if you’re a librarian or educator considering implementing Connected Learning, please don’t be overwhelmed by the multiple spheres and various possibilities. If you’re building from youth interests, you can bring in the other components over time.

The creators of Project READY had the same problem: we shared frameworks that it’s easy to feel you must implement perfectly or not at all. We discussed Dr. James A. Banks’s framework for multicultural education, which has four levels of integration, ranging from the contributions approach (what we sometimes call the “heroes and holidays” approach to culture) all the way to the social action approach, in which students actually work to solve social issues. It can be easy to see models where youth contact government officials and make social change and think, “Well, I don’t have what I need to do that, so this model has nothing for me.” But there are two other levels in the model, the additive approach incorporating new multicultural content without changing curricular structure and the transformation approach which involves reshaping curriculum to center multiculturalism rather than adding it on. If your current approach is at the contributions level, moving to the additive approach is preferable to giving up on the whole framework.

As with improving the nutritional quality of your diet, adding more movement into your day, or any habit change, moving in the right direction is preferable to not moving at all. For example, if you learn you have some youth at your library interested in cosplay, maybe you start by hosting some simple no-sew project events. Then over time you can find out if there is a cosplay charity organization in your area and find out if any of those cosplayers would be interested in sharing their expertise, and the youth might build relationships with them as well as each other. And those cosplayers might then introduce the youth to opportunities like participating in contests or engaging in charitable cosplay themselves. You didn’t start with all three parts, but you moved in the direction of Connected Learning at each stage.

Future Directions for Connected Learning in Libraries

This is the fourth post in a series contextualizing my position as a researcher of connected learning.

Here are all the posts published so far:

There are a number of opportunities for connected learning to grow in libraries. Here I’ll discuss some of them, beginning with the one most relevant to my current work.

Research-Practice Partnerships Research-Practice Partnerships allow library professionals to develop connected learning environments and programs in collaboration with researchers of learning and information sciences. The project I’m working on, Transforming and Scaling Teen Services for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (TS4EDI) is one such partnership. Myself and other researchers at the Connected Learning Lab, including PI Vera Michalchik and Research Manager Amanda Wortman, are working with state librarians in Rhode Island and Washington first to identify barriers and challenges to libraries creating CL environments and programs and then to develop resources to help library professionals overcome those barriers and challenges. The state librarians will recruit local public librarians in their state to be part of this partnership, and those public librarians will recruit youth to participate, as well. Other examples include the ConnectedLib project and the Capturing Connected Learning in Libraries project.

Brokering Youth Opportunities in Libraries Connected learning research over the past 10 years has highlighted the importance of caring adults or peers as brokers or sponsors for youth as they build their networks surrounding an interest. These brokers/sponsors can connect youth with other people and resources to help them expand their network and identify opportunities for learning and achievement related to their interest. Current research literature doesn’t explicitly offer guidance on brokering as a distinct activity, investigate the extent to which librarians currently act as brokers, or illuminate how youth may serve as peer brokers in the library setting. Research-practice partnerships and library professional-led professional development could address these questions.

Bringing Connected Learning to School and Academic Libraries So far, connected learning has been documented mostly in informal settings. A few studies have looked at connected learning in formal settings, but those tend to be individual classrooms rather than school or academic libraries. One area that offers potential for CL in these settings is the connection between interests and information literacy. This was the focus of my dissertation, in which I examined the information literacy practices of cosplayers. Cosplayers engage in connected learning as they learn about their interest, build relationships with each other, and find opportunities to contribute to the cosplay community or even become professional cosplayers. Throughout these elements of connected learning, cosplayers engage in information literacy, identifying resources, evaluating them, and even creating new resources. Because school and academic libraries are the primary center for information literacy education in their institutions and because they are not tied to a specific academic discipline, they have the potential to create opportunities for connected learning as learners build their information literacy practices.

That’s all for this series of blog posts, but I expect to write a lot more about connected learning through the course of my work at the Connected Learning Lab, so if you find this interesting, stay tuned!

Connected Learning in Libraries: Changes and Challenges

This is the third post in a series contextualizing my position as a researcher of connected learning. Here are all the posts published so far:

While libraries are poised to be environments conducive to connected learning, they may need to undergo further shifts to expand their support for connected learning. This involves a number of considerations:

Resources. Library professionals must consider not only physical and digital resources, but human resources as well - using “resource” to describe a person the same way we might use it to describe a book or a website. Library professionals can serve as a point of connection between learners, mentors, and other people in the environment beyond the specific context of the connected learning activities.

Technology and space. Current library policies may need to be updated to enable learners to engage in shared practices, socializing, collaborating, and publishing their work online.

Evaluation. Libraries have traditionally focused on quantitative measures of impact, such as how many people attended a particular program. These measures may not be sufficient to capture the impact of connected learning. Measures of connected learning need to capture the way learners move with their learning across settings beyond spaces controlled by the library; identifying specific desired outcomes can facilitate capturing evidence of and communicating the impact of a program. Qualitative data such as interviews or open-ended survey questions may capture this impact better than or alongside quantitative measures.

Role of library professionals. Library professionals must learn to consider themselves as sponsors and brokers of youth learning rather than mentors or authority figures. This means helping youth find other people and communities to support their learning and focusing on enhancing learning rather than enforcing behavior-based policies.

Program design. To create programming that fosters connected learning, library professionals may need to co-design with youth rather than deciding programming in advance and offering it to youth without their early input.

Competencies. The creators of the ConnectedLib project identified the following necessary competencies for library professionals to support youth’s connected learning:

Professional development. Library professionals often will not have been trained in these competencies during their education, so they may need to continue their own learning via in-house professional development, programs provided by professional organizations, open online learning resources, and formal educational experiences. The ConnectedLib toolkit is one example of an open online learning resource directed at meeting this need, while the University of Maryland’s Youth Experience In-Service Training is an example of a formal educational experience designed to build these competencies.

I identified these potential shifts to library practices in response to a number of challenges libraries face in developing and implementing connected learning programming, including:

Attracting teens to skill-building programming. For some advanced interest-based experiences, youth need a foundational set of knowledge. For example, to create a sophisticated video game, a teen would first need a foundational understanding of game design and computer programming. It is a challenge to attract novice learners to this kind of programming.

Working with technology. Library professionals may lack the digital tools they need due to library policy, may know how to design or facilitate technology-focused or -infused programming, or may not feel comfortable acting as effective digital media mentors.

Unfamiliarity with the Connected Learning model. Library professionals may struggle with integrating all the different spheres and elements of the model. They may not have the knowledge, skills, or training they need to successfully implement the model.

Culture clashes. Teen culture may sometimes clash with library culture, requiring library professionals to negotiate these conflicting cultures to create programming that has a strong impact in teens’ lives.

The next and, I think, final post in this series will address future directions for connected learning in libraries.

How Connected Learning Happens in Libraries

This is the second post in a series contextualizing my position as a researcher of connected learning. Here are all the posts published so far:

The first element of connected learning is interest. Libraries explicitly support the exploration of personal interests in both their collections and their programming. The second element is relationships. Libraries are intergenerational spaces that can be (but aren’t always) inclusive of people from nondominant groups. Libraries can serve as a bridge that connects formal and informal learning. Libraries are increasingly spaces where youth can have shared experiences creating new knowledge. They are third places, neither school nor home, where youth can gather, connect around their shared interests, and meet adult mentors and sponsors who can help them leverage a variety of resources in pursuing those interests.

A note about third places in the time of COVID-19: For many of us (the luckiest among us, I would argue), there is only one place: home, which is also work, which is sometimes also school, which is also where we do whatever social activity we do. This is certainly true for me. That said, online library programming can act as a virtual third space, a place to go for something that isn’t all about home or work responsibilities. I’ll be interested to see how scholarship around this shift evolves. A quick search for “‘third places’ COVID” on Google Scholar demonstrates that scholars are already thinking about this, including in the specific context of public libraries. I am exercising extreme restraint to not jump down a rabbit hole of exploring that research right now.

There are some examples of connected learning happening in both public and school library spaces. If you’d like to explore them, here are some links:

The next post in this series will discuss some of the challenges of creating connected learning experiences in libraries and some shifts libraries may need to undergo to provide more connected learning experiences.

What is Connected Learning?

I start working remotely for the Connected Learning Lab tomorrow and while a lot of people are excited for me, most of them don’t actually understand what I’m going to be doing. So I’m writing a blog series that I hope will explain that somewhat, and this is the first post. If you’ve read my comps chapter on Connected Learning or seen my Connected Learning and the IndieWeb talk, some of this will be familiar.

Connected learning can be conceived of in three ways: as a type of learning experience that occurs spontaneously, as an empirically-derived framework for describing that type of experience, and as a research and design agenda aimed at expanding access to that type of learning experience. My brother-in-law, P., is actually a phenomenal example of a Connected Learner.

In high school and college, P. was interested in playing guitar. He started hanging out at a local guitar shop, connecting with a community there of peers and mentors. Through the connections he made, he was offered the opportunity to be lead guitarist for a tribute band, and that job took him all over the world. He has since embarked on a different but related career, working in media law. This area of law might not have been of interest to him if he hadn’t had experience working in the music industry.

That’s an example of a spontaneously occurring connected learning experience. From experiences like this, scholars have created a model to describe connected learning. This model includes three elements of connected learning: interests, relationships, and opportunities. P. was interested in music, built relationships at the guitar shop, and it led him to opportunities to perform as part of a working band and become a lawyer.

Image Source: The Connected Learning Alliance

This type of experience is easier to access with more financial and temporal support; the research and design agenda surrounding connected learning is an equity agenda that aims to broaden the availability of this kind of experience, making it possible for nondominant youth who might require additional support to access connected learning. One way to do that is to bring this kind of experience into public spaces serving nondominant youth - public spaces like libraries.

The work I’m doing with the Connected Learning Lab is part of a grant funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services examining key needs for teen services in libraries:

(1) the challenges library staff face in designing and implementing CL programming for underserved teens and the means for overcoming these challenges, (2) ways library staff can use evaluative approaches to understand youth needs in CL programming, and (3) the means of demonstrating the value of CL programs and building stakeholder support for increasing their scope and scale, particularly to serve equity goals.

The products of this research will include

training modules, guidebooks, mentoring supports, case studies, videos, practice briefs, topical papers, and blogs.

These are some of my favorite kinds of things to create, so I’m extra excited.

My next post in this series will talk about how Connected Learning is already happening in libraries, with some examples from actual libraries.

Memo: Affinity Spaces

Gee introduced the concept of affinity spaces in his book Situated Language and Learning: A Critique of Traditional Schooling (2004). Affinity spaces are a subset of what Gee calls a semiotic social space, a type of space for interaction with an infrastructure incorporating content, generators, content organization, interactional organization, and portals. Content is what the space is “about,” and is provided by content generators. Gee uses the example of a video game (the generator), which generates a variety of content (words, images, etc.). The space is then organized in two different ways: content is organized by the designers, whereas interaction is organized by the people interacting with the space, in how they “organize their thoughts, beliefs, values, actions, and social actions” (Gee, 2004, p. 81) in relationship to the content. This interaction creates a set of social practices and typical identities present in the space. The content necessarily influences the interaction, but interaction can also influence content. For example, with a video game, player reactions to the game may influence future updates to the game. Finally, Gee defines portals as “anything that gives access to the content and to ways of interacting with that content, by oneself or with other people” (Gee, 2004, p. 81). In Gee’s video game example, this could be the game itself, but it could also be fan websites related to the game. Portals can become generators, “if they allow people to add to content or change the content other generators have generated” (Gee, 2004, p. 82). A video game website might include additional maps that players can download and use to play the game or offer recordings of gameplay to serve as tutorials or entertainment. A generator can also be a portal; for the video game example, the game disc or files both offer the content and can be used to interact with the content.

Gee builds on this description of a semiotic social space to describe “affinity spaces,” a particular type of semiotic social space that young people today experience often. The “affinity” to which Gee refers is not primarily for the other people in the space, but for “the endeavor or interest around which the space is organized” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 84). He defines an affinity space as a space that has a number of features:

A space does not need to have all of these features to be considered an affinity space; rather, these features can be considered as a measure of the degree to which a space is an affinity space or how effective an affinity space it is. Affinity spaces can be nested within one another (J. P. Gee, 2017); for example, a website devoted to The Sims video game fanfiction would be an affinity space itself, while also being part of the broader The Sims affinity space, the gaming affinity space, and the fanfiction affinity space. At first glance, an affinity space may seem very similar to a community of practice as described by Lave and Wenger (1991); Gee argues, however, that defining a community implies labeling a group of people, including determining “which people are in and which are out of the group, how far they are in or out, and when they are in and out” (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 78). Talking about spaces instead of communities removes this concern of membership; people who are present in a space may or may not be part of a community. Further, Lave and Wenger’s original conception of communities of practice described movement from peripheral participation for what Gee would call “newbies” to central participation as “masters,” while in affinity spaces, newbies do not need to be apprenticed to masters to become deeply involved in the space’s activity.

Gee (2004, 2005) offered the concept of affinity spaces as part of a critique of how schooling works; he argues that “people learn best when their learning is part of a highly motivated engagement with social practices which they value” (Gee, 2004, p. 77) and suggests that affinity spaces facilitate this kind of engagement. Gee argues that as young people encounter more and more affinity spaces, they see a “vision of learning, affiliation, and identity” that is more powerful than what they see in school (J. P. Gee, 2004, p. 89). He suggests that educators can learn from the design and construction of affinity spaces.

After Gee introduced the concept of affinity spaces, scholars investigated specific affinity spaces and what lessons they might have for educators working in the areas of literacy (Rebecca W. Black, 2007, 2008; R. W. Black, 2007; Lam, 2009), science (Steinkuehler & Duncan, 2008), and mathematics (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2009). These studies supported Gee’s original conception of affinity spaces, finding many features of affinity spaces in their research settings, which included fanfiction websites (Rebecca W. Black, 2007, 2008; R. W. Black, 2007), anime/manga discussion forums (Lam, 2009), and massively multiplayer online games and their related discussion forums (Steinkuehler & Duncan, 2008; Steinkuehler & Williams, 2009).

Refining the Concept of Affinity Space

As the technology available for online participation shifted from predominantly individual websites or forums to predominantly social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Youtube, online affinity spaces shifted as well. In the introduction to the book Learning in Video Game Affinity Spaces, Hayes and Duncan (2012) point out that, like online culture more broadly, online affinity spaces present a “quickly moving target” (p. 10) for study. They call for a refined and expanded conception of affinity spaces in light of this fact. While Gee’s (2005; 2004) original conception of affinity spaces consisted of eleven features that may or may not be present in any given affinity space, in his afterword to Hayes and Duncan’s (2012) book, he identifies five key features of what he now calls “passionate affinity spaces”:

Gee and Hayes (2010, 2012, 2011) distinguish between “nurturing” and “elitist” affinity spaces. Building on Gee’s earlier work and drawing on studies of fan sites associated with the computer game The Sims, Gee and Hayes “identify features of what [they] call nurturing affinity spaces that are particularly supportive of learning” (p. 129). They describe the following fifteen features of affinity spaces and the ways they are enacted in nurturing affinity spaces:

Referring to the work of Gee and Hayes, Hayes and Duncan point out that “…while elitist spaces are sites of very high knowledge production, they tend to value a narrow range of skills and backgrounds, have clear hierarchies of status and power, and disparage newcomers who do not conform to fairly rigid norms for behavior” (2012, p. 11). Gee and Hayes (2010, 2011, 2012) suggest that nurturing spaces are more conducive to learning than elitist spaces.