This is the third post in a series contextualizing my position as a researcher of connected learning. Here are all the posts published so far:

- What Is Connected Learning?

- How Connected Learning Happens in Libraries

- Connected Learning in Libraries: Changes and Challenges

While libraries are poised to be environments conducive to connected learning, they may need to undergo further shifts to expand their support for connected learning. This involves a number of considerations:

Resources. Library professionals must consider not only physical and digital resources, but human resources as well - using “resource” to describe a person the same way we might use it to describe a book or a website. Library professionals can serve as a point of connection between learners, mentors, and other people in the environment beyond the specific context of the connected learning activities.

Technology and space. Current library policies may need to be updated to enable learners to engage in shared practices, socializing, collaborating, and publishing their work online.

Evaluation. Libraries have traditionally focused on quantitative measures of impact, such as how many people attended a particular program. These measures may not be sufficient to capture the impact of connected learning. Measures of connected learning need to capture the way learners move with their learning across settings beyond spaces controlled by the library; identifying specific desired outcomes can facilitate capturing evidence of and communicating the impact of a program. Qualitative data such as interviews or open-ended survey questions may capture this impact better than or alongside quantitative measures.

Role of library professionals. Library professionals must learn to consider themselves as sponsors and brokers of youth learning rather than mentors or authority figures. This means helping youth find other people and communities to support their learning and focusing on enhancing learning rather than enforcing behavior-based policies.

Program design. To create programming that fosters connected learning, library professionals may need to co-design with youth rather than deciding programming in advance and offering it to youth without their early input.

Competencies. The creators of the ConnectedLib project identified the following necessary competencies for library professionals to support youth’s connected learning:

- …they must be ready and willing to transition from expert to facilitator…

- …[they] need to apply interdisciplinary approaches to establish equal partnership and learning opportunities that facilitate discovery and use of digital media…

- …they should be able to develop dynamic partnerships and collaborations that reach beyond the library into their communities…

- …they should be able to evaluate connected learning programs and utilize the evaluation results to strengthen learning in libraries… (Hoffman et al., 2016, p. 19)

Professional development. Library professionals often will not have been trained in these competencies during their education, so they may need to continue their own learning via in-house professional development, programs provided by professional organizations, open online learning resources, and formal educational experiences. The ConnectedLib toolkit is one example of an open online learning resource directed at meeting this need, while the University of Maryland’s Youth Experience In-Service Training is an example of a formal educational experience designed to build these competencies.

I identified these potential shifts to library practices in response to a number of challenges libraries face in developing and implementing connected learning programming, including:

Attracting teens to skill-building programming. For some advanced interest-based experiences, youth need a foundational set of knowledge. For example, to create a sophisticated video game, a teen would first need a foundational understanding of game design and computer programming. It is a challenge to attract novice learners to this kind of programming.

Working with technology. Library professionals may lack the digital tools they need due to library policy, may know how to design or facilitate technology-focused or -infused programming, or may not feel comfortable acting as effective digital media mentors.

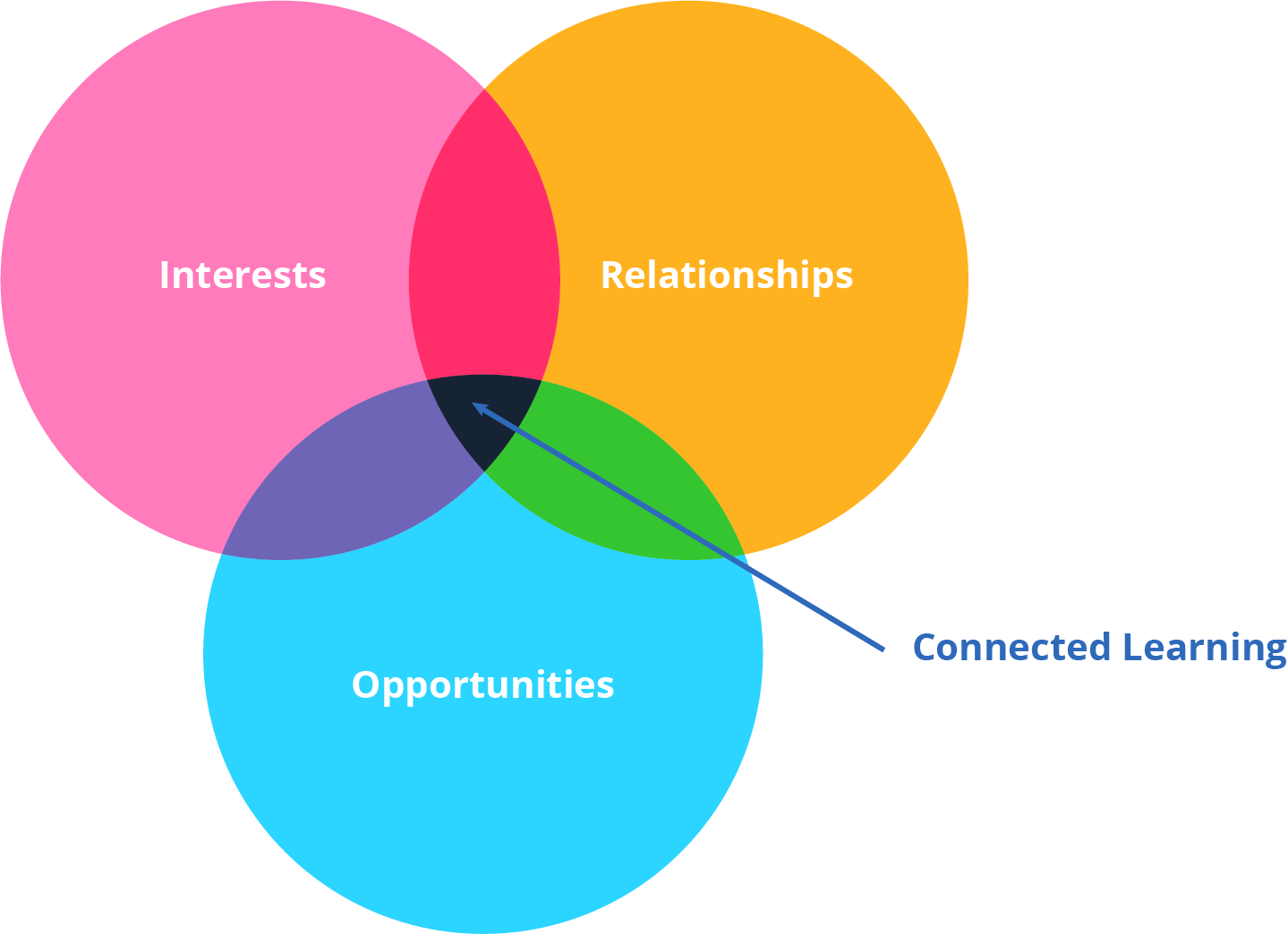

Unfamiliarity with the Connected Learning model. Library professionals may struggle with integrating all the different spheres and elements of the model. They may not have the knowledge, skills, or training they need to successfully implement the model.

Culture clashes. Teen culture may sometimes clash with library culture, requiring library professionals to negotiate these conflicting cultures to create programming that has a strong impact in teens’ lives.

The next and, I think, final post in this series will address future directions for connected learning in libraries.