🎵📽📚 I don’t know if it’s a problem or a good thing that when my mind can’t come up with a topic to blog about and I’ve committed myself to blogging (as I’m now trying to do first thing everyday when I sit down to work), I just jump in and treat my blog like morning pages. Which is fine unless I’m working on a blog post that I’m not ready to write yet and that is sort of occupying my stream-of-consciousness. Which is what’s happening right now: later, I’ll write a post about reclaiming my Spotify recommendations - Discover Weekly and Daily Mixes - from my kid’s music tastes, and the different tools and articles I’m using to do it. But I’m not there yet.

I can talk about music, though. That’s a thing. So, I don’t consider myself a person who has well-defined musical tastes. When I was growing up, my parents had a Columbia House membership, and I listened to their Gold & Platinum tapes a fair amount. I feel like I mined their tapes for other stuff, too: Styx’s Kilroy Was Here, Culture Club’s Colour by Numbers, a Peter and the Wolf that they transferred from vinyl to cassette (I don’t know which one, but my money’s on Cyril Richard), and The Irish Rover’s The Unicorn, which I guess was my grandfather’s album and not mine. I also had a Mousercise album that familiarized me with a bunch of Disney songs from movies I may or may not have seen, and the songs in the Totally Minnie TV special: “Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart,” “I Only Have Eyes for You,” “Let’s Hear It for the Boy,” “Nasty,” and “Eat It,” among others.

It was probably this early that I started getting into showtunes (my parents took me to see A Chorus Line when I was 3) and film scores, especially the John Williams oeuvre. These were always shared family experiences, and I loved them.

The first album that I remember as really being something I listened to because I chose it was Madonna’s Like a Virgin. I would put this on and dance, and of course had no idea what most of the songs were about. In fourth grade a friend introduced me to the movie Beaches, which brought me into the Bette Midler fold. I think it’s kind of hilarious that my mom was relieved when I traded Madonna for Bette Midler. I don’t think she’d done her research.

Also when I was in fourth grade, I first encountered The Phantom of the Opera and I fell in love right away. My parents had always enjoyed and shared Jesus Christ Superstar with me.

Around 1991, I started paying attention to pop hip-hop and R&B, and I think those are the genres that still speak to my heart in a very real way, especially R&B. In particular, I loved Kris Kross, En Vogue, Vanessa Williams’s “Save the Best for Last”, Des’ree’s “You Gotta Be,” and pretty much everything Boyz II Men. I briefly had a quick interest in Tim McGraw due to a friend liking him, but then returned to R&B. I also choreographed a secret dance to Paula Abdul’s “The Promise of a New Day” that no one ever saw.

Between Highlander and Wayne’s World, Queen got a lot of play. I think my mom liked them long before I knew I did.

In high school, I went back to Bette Midler and doubled down on the showtunes my parents had introduced to me in childhood, plus new shows. This is what I think of as my “musical taste” - a preference for showtunes to pretty much all genres, including R&B. My friends were into alternative from 1992 on, probably, and I can sing at least a few bars of every song on Spotify’s 90 Pop Rock Essentials playlist, less because I actually like them than because they were the big radio hits when I took Driver’s Ed.

My senior year of high school, I started dating W. and he loaned me CDs for many musicals, expanding/deepening my showtune horizons even further, and I really sort of locked in on showtunes until I was 20 or 21, when my participation in Domain Grrl culture led me to take an interest in more contemporary music as well as some older artists, and that’s when I got into artists like Michelle Branch, Lucy Woodward, Evanescence, and Jeff Buckley, with a little Dave Matthews Band thrown in because why not. I really loved Shakira’s “Underneath Your Clothes at this time, too.

Then I took a turn into punk/punk-influenced stuff, digging into The Sex Pistols, Me First and the Gimme Gimmes, Jimmy Eat World(not sure that counts as punk, but I listened to it around this time), Superchunk, and older Goo Goo Dolls stuff. Plus I picked up a little bit of hairband stuff, mostly Poison’s Greatest Hits. Opposites, right?

I also listened to a lot of what might best be called “Buffy rock” at this time - bands featured on or somehow related to Buffy the Vampire Slayer and/or Angel: Velvet Chain, Darling Violetta, Four Star Mary, Common Rotation, and Kane. (And I guess a little Ghost of the Robot, and actually a lot of Tony Head and George Sarah’s album Music for Elevators, especially the track “Last Time,” over and over on repeat one until it made my friends very tired of it.)

W. gave me Cake’s Fashion Nugget and They Might Be Giants’s Flood around this time, both of which I love. Also, my friend A. gave me a copy of Eisley’s Room Noises, which I still love and find magical.

I retreated back to showtunes until around 2012, when I made friends with author Nathan Kotecki, who gave me a giant mix of all the goth/darkwave music that inspired him as he wrote his first novel, The Suburban Strange. In a real sense, this felt like going home, and when I then followed that up by listening to all the music Jillian Venters (also a friend) recommends in her book Gothic Charm School, I decided that Switchblade Symphony was my new favorite band. Which makes sense, because it’s a team up of a film composer and a musical theater performer.

And that’s where we are today. Writing this has helped me realize that actually, I totally have defined musical tastes. Look for tips on teaching Spotify to follow.

Cosplays of 2019: Luna - Cat Version (Sailor Moon), Ariel (Ralph Breaks the Internet), Wednesday Addams (The Addams Family, 1991 film)

Cosplays of 2019: Luna - Cat Version (Sailor Moon), Ariel (Ralph Breaks the Internet), Wednesday Addams (The Addams Family, 1991 film)

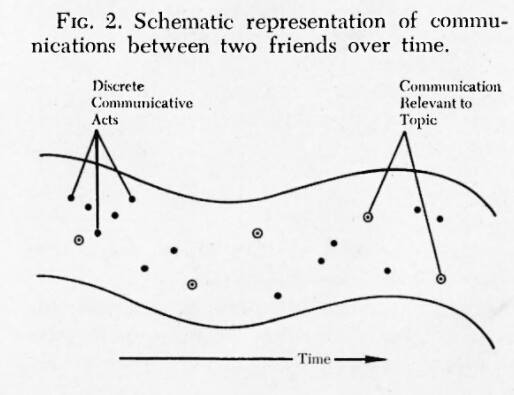

Figure from “Question-Negotiation and Information Seeking in Libraries,” Robert S. Taylor, College and Research Libraries 29(3), 178-194[/caption]

Figure from “Question-Negotiation and Information Seeking in Libraries,” Robert S. Taylor, College and Research Libraries 29(3), 178-194[/caption]